Graffiti, Laundry, Fado: Alfama (Part 1)

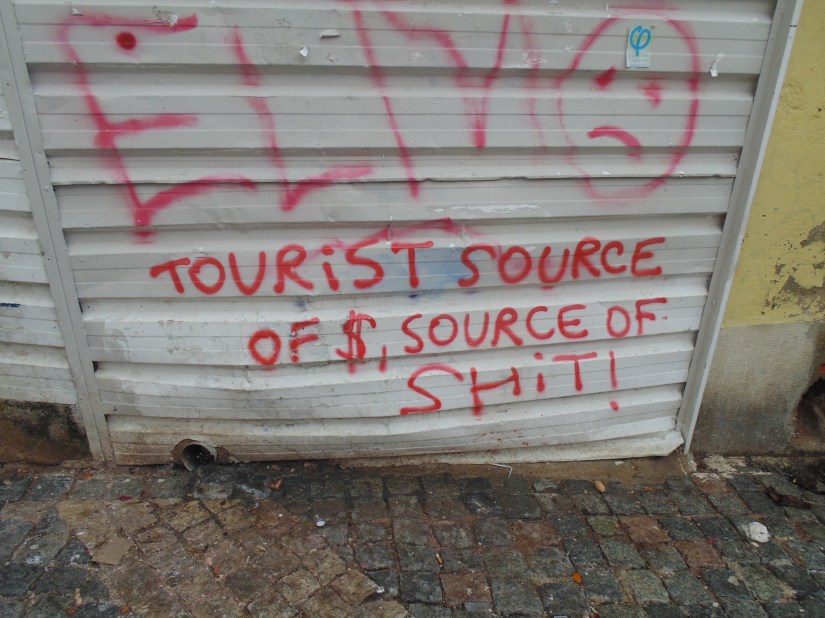

On a small square in Alfama, against the side of a metal door someone had spray-painted the phrase “Tourist source of $, source of shit.”

The sign was both insulting and appropriate, given how touristy Alfama is. As one of Lisbon’s most authentic and picturesque neighborhoods, it’s packed with tourists like us ready to capture on camera every wrought-iron balcony, every house paneled in azulejo tiles. Like any major city, Lisbon has no shortage of graffiti but the Alfama neighborhood seemed especially hard-hit. A few days before, on our ascent to the castle, we’d passed through a narrow alley of ruined houses, many of which had been transformed into impromptu canvases for street art.

Those markings, however, I’d describe more as “art” than straight-up graffiti, which I’ll here define by its simplicity of design. (I’m not trying to weigh in on the art-vs-graffiti debate, merely suggesting that it takes more time and effort to design a Guernica-style mural than to spray words across a wall.) Much of the graffiti was more in keeping with the “tourism as shit” variety although perhaps not as extreme in its sentiment. I asked our guide, Joseph, what the purpose behind these frequent markings were. He scowled. “Stupidity. People are like dogs leaving marks.”

I’ve no doubt “marking” was a motive, although I’m less sold on the “stupidity” part. Sure, some of the marks were probably just – stupid, but “tourism as shit”, for its relative simplicity, may also have a more overt political meaning. That it was in English, and not Portuguese, gives some idea as to its intended audience.

I wrote earlier about how Alfama is one of my favorite neighborhoods in Lisbon but there is something dark and somewhat twisted behind Alfama’s charms. For centuries, Alfama was a district for the poor. The high, narrow houses packed tightly together, with charismatic laundry lines draped between balconies, were the refuge for multi-generations of immigrants, sailors, and religious minorities.

Today, Alfama is still associated with the economically poor and disenfranchised, although it’s also promoted as Lisbon’s most authentic neighborhood. Tourists are encouraged to lose themselves in the labyrinth of narrow lanes, the hole-in-the-wall restaurants, and the tiny bars where locals sip ginja (sweet cherry liquor, which I highly recommend) at all hours of the day.

To accommodate these tourists, other agents are now taking over the territory: beds and breakfasts, upscale restaurants, boutique shops and hotels. Tourism might bring in money, but it also brings with it gentrification. Alfama seems caught between the worlds that many American cities also in the process of gentrification are caught between: poverty and privilege, wealth and opportunity verses stagnation. As tourists, we come to view the charm, but we are also viewing this divide. We bring money, but we also bring change, and not always for the better or the benefit of everyone equally.

Near the end of our walking tour, Joseph took us to what he called a neighborhood laundry room. The room was on the ground floor of a white-washed house. Inside were rows of stone basins with faucets, separated by line after line of drying rugs and bedsheets. A few women mingled about, elbows deep in basins. Many who came here, Joseph said, worked for the beds and breakfasts, but some came to scrub rugs or other items they couldn’t wash easily at home.

Oddly and uncharacteristically for me, I didn’t take any pictures. I don’t know if these women were there cleaning their own dirty laundry or the laundry of others. Either way, the idea of recording their daily act of existence as part of my sight-seeing just didn’t appeal to me.